- Home

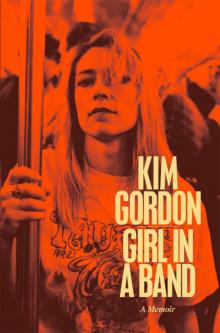

- Kim Gordon

Girl in a Band Page 7

Girl in a Band Read online

Page 7

York University had just rolled out a brand-new music department—there were always small concerts going on, including performances of works by the resident composers. I saw lots of great contemporary music while I was there, from the Art Ensemble of Chicago to the premiere of John Cage and David Tudor’s bicentennial Rainforest piece, though mostly I was bored, making minimalist, gooey, unstretched paintings, with no instructor. Rather than write a paper for my film class, I decided to make a silent surrealist film about Patty Hearst, who’d just been let go by the Symbionese Liberation Army. With her shoulder-length black hair, my fellow bandmate Rae made a picture-perfect Patty. Felipe, who was also a filmmaker, shot and helped me edit the movie. George Manupelli lent me a sixteen-millimeter camera and film. I was immersed in art, but unformed and trying anything and everything.

But I was homesick, too, less and less happy as the bleak Toronto winter moved in. Without the benefit of California sunshine, my hair grew darker and darker, and I had no idea how to dress for the cold. When the school year ended, I drove home to California, and instead of making plans to return to York, I began attending Otis Art Institute in downtown L.A. At $600 a semester, Otis was undistinguished but cheap. I lived here and there: Culver City, Silver Lake, Venice again. To pay my bills, I found work in a little Indian restaurant called Dhaba, which served home-cooked, endlessly simmered Indian food. My parents weren’t all that happy—they wanted me to finish what I’d started at York—but Otis changed my life.

For one thing, I became very close to John Knight, a conceptual artist with an architectural background who’d come to Otis as an artist in residence and taught a seminar. I was twenty-four, he was thirty-one. John was captivating, the first real mentor I’d ever had. I’d never met anyone like him, and the landscape of L.A. was our playground for any kind of mutual intellectual discussion. John was born and raised in L.A., and his art practice centered on whatever political and social forces were inherent in the design, architecture, history, and function of the visible world, while simultaneously taking in a viewer’s relation to the art or the spectacle in question. His career has recently become more visible and influential.

Then, though, he was an intellectual light, and a minor renegade, having been kicked out of Otis in his day for cutting the school’s hedges as part of a sculpture. He and I spent hours driving around L.A., looking at assorted local oddities and suburban inventions, drive-throughs and outlying tract-house developments with their small deadening model homes. He showed me neighborhoods on the Eastside I’d never seen before. As usual, everywhere and everything in L.A. was either a blunt, bizarre juxtaposition—an old quaint one-story ranch house squeezed in beside a mammoth McMansion—or a potential picnic destination, whether it was the Huntington gardens or a green grass patch fronting some new development. No matter where I go in my life, visually L.A. will always be my favorite place on earth.

John Knight taught me that anything—a car, a house, a lawn—could be seen and talked about in aesthetic terms. He introduced me to conceptual art, showed me how all art derives from an idea. Every week, his class met at a different place, typically one of his students’ houses or apartments. We would discuss in detail whatever came up or whatever happened to be around—what kind of font a typewriter used, for example. Was it Helvetica, or Futura, or a less predictable, flouncier typeface? This may sound trivial, but it taught us that detail mattered—in John’s own work, as in most conceptual art, detail practically becomes the work—but big things mattered too. It was John, after all, who told me I had enough credits to petition my way out of Otis, which turned out to be surprisingly easy to do. But before that happened, Dan Graham came along.

13

IN 2009, THURSTON and I were asked to appear at SculptureCenter in Long Island City, which was honoring Dan Graham as part of their annual fund-raising gala. Knowing how obsessed Dan is with astrology, I asked a friend who does charts professionally to interpret his chart for us. He did, and we incorporated snippets in our introduction—Capricorn rising, Aries sun, ruled by Mars in Gemini conjunct Jupiter in the Sixth House, and so on—before Dan finally came onstage. We also played his favorite song by the Fall, “Repetition,” lead singer Mark E. Smith being one of Dan’s longstanding Marxist punk heroes.

Dan was a peer of John Knight’s, though slightly older. John had spoken a lot about Dan’s work in class, enough for me to know that Dan was a hero underdog of the contemporary art world. When Dan spoke at CalArts that spring, I followed John’s advice and went to see him, not knowing all the roles he would play in the next part of my life.

Dan was an original. In 1964, he’d launched the first conceptual art show in New York in the John Daniels Gallery, an exhibition space he opened with a few friends. At the time he spoke at CalArts, his best-known work was Homes for America, a series of photos of New Jersey tract housing that Arts magazine published in 1966. The development, where Dan had moved when he was three, was one of America’s first-ever tract housing developments. Critics referred to Dan’s work as the first-ever “minimalist photos.” Those little houses were sad and similar, bland, box-cut, and haunting. They reminded me of a family of low-to-the-ground arrowheads. Dan later described Homes for America as a “fake think-piece.”

Dan was, and still is, a volatile, wild thinker and communicator, a self-educated social anthropologist who spent his teenage years poring through the works of Margaret Mead, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Wilhelm Reich. Reading an essay Dan once wrote for Fusion magazine about Dean Martin, where he compared Dean Martin with his cigarette and cocktail glass to Brecht and Godard, and called Martin’s persona both a “myth” and a “scaffold,” made me realize anyone and anything could be made interesting.

Dan got a huge kick out of astrology’s dime-store, lowbrow, circus-show vibe, a six-thousand-year-old art and science of observation doomed to end up in the twenty-first century on the slippery back pages of women’s magazines. Astrology wasn’t remotely intellectual, and though Dan never studied the planets in depth, he got pleasure out of placing a great trashed knowledge into a formal dialogue. Peppering his conversation with zodiacal references was Dan’s way of being a brat, a punk. It gave him shortcuts to understanding people, helped him elbow up close to them. Some of Dan’s later work, which explored the relationship of the artist to the audience as a mirror, matched uncannily what he told me was his own astrological makeup, how he absorbed the qualities of whoever he was talking to at the time.

I was in the audience when Dan showed up to lecture at CalArts. I found him unforgettable. With his head cocked to one side, his fingers winding around sickles of his own hair, Dan spoke quickly and haltingly, lobbing random, curvy perceptions into the audience left and right. My dad’s sociology background probably made Dan’s work all the more appealing to me, but I also knew I’d never been in the presence of someone so brilliant.

Among the subjects Dan talked about during this lecture were the origins of punk rock. Who started it? Was it Malcolm McLaren or someone else? Mike Kelley, who was also there that night, flipped up his hand and began arguing the point. As a Detroit native, Mike believed that Iggy Pop and the Stooges were the first-ever punk rockers, and that Detroit was ground zero for punk music. Dan acknowledged that point, and also talked about how McLaren had gone to New York and witnessed Richard Hell and Television at CBGB with their torn attire and safety pins and took it back to England, mixing it with Situationism. Mike and Dan were essentially in agreement but nitpicking over details. Their back-and-forth grew more intense, Dan’s voice getting higher and louder, and Mike’s growing agitated. It’s a conversation I’ve witnessed since many times. What was most clear about that day and that exchange was how passionate Dan and Mike both were about music and how, if given the choice, they’d both much rather talk about rock and roll than about art.

When the lecture ended, I introduced myself to Dan, and also to Mike. A few months later, Mike and I became friends and then briefly romantically involved. Dan cam

e back out to L.A., and I remember taking him to a community music event in a park in Orange County. Every weekend the park hosted a different music theme. That week’s theme was punk, and specifically Black Flag. Families dotted the hyper-green grass, spread out on blankets and plastic chairs with their kids.

At the time, the lead singer for Black Flag was a guy named Keith Morris. I liked Keith. Unlike other punks of that era, he avoided dressing in stylized punk fashion. In his ratty camo jacket, he looked more like a dream-haunted military vet. When Black Flag started playing, a few of the little kids in the audience started throwing bottles at the stage. The emcee finally came onstage to warn the audience that if it didn’t simmer down, he’d end the show right there. In response, everyone began applauding. Before Orange County became known as the cooler-sounding O.C., it was just known as conservative.

For years afterward, Dan talked about that Black Flag concert. Southern California was a never-ending source of amusement for him: its pockets of sun-struck conservatism; the bizarre good manners and politeness, as if everyday life had been reduced to a series of curves, blunted, similar, unchanging.

It was the beginning of two of the most important relationships in my life. Mike’s influence on me, if there is one, was subtle, as he and I were more like peers. I got a lot of pleasure out of seeing another artist making work that looked nothing at all like conceptual art, that was unconventional, that mixed together high and low. Through Mike I also met some important people in my life, like Tony Oursler, the multimedia and video installation artist, who is both a generous person and an imaginative genius, and who always supported whatever I was doing. Tony later helped me shoot and edit a mini-documentary I wanted to make about the club Danceteria and also shot an incredible video for the Sonic Youth song “Tunic.” I also collaborated with Tony and the film director Phil Morrison on a project called Perfect Partner, a multimedia extravaganza I concocted and performed more than a half dozen times in Europe and once in the U.S. I had written a script based on car ad copy that was intended to be a takeoff on Nouvelle Vague. Michael Pitt acted in it. My improv quartet performed a live, roughly scripted soundtrack between two screens, one displaying backgrounds that Tony had filmed, and the other, front and center and semitransparent, showing the action and the actors that Phil had shot. The effect was like a giant 3-D Tony Oursler piece. Tony and I still collaborate on projects and remain friends.

Dan’s influence was stranger, harder to define. In a concrete way, Dan turned me on to any and all No Wave bands that were playing in downtown New York on any given night, and I also loved the poppy-but-deep way he wrote about or dramatized psychological or sociological issues, like the idea of viewing art as a kind of voyeurism. Dan’s passion for music was as strong as his interest in art, and rock and roll often found its way into his subject matter. Once Dan told me he wished he could make art that was like a Kinks song. (A lot of artists listen to music while they work, and many think, Why can’t I make art that looks as intense as the sounds I’m hearing? I don’t have an answer.)

14

Photo by Felipe Orrego

DRIVING DOWN the West Side Highway, I still get the same thrill I did when I first drove over the bridge into Manhattan in 1980. I don’t think I’ll ever lose that feeling. Today the Henry Hudson Parkway is buffed, a tarred straightaway for little low-slung cars and Range Rovers with Connecticut and Westchester plates. Across the river, New Jersey construction stabs up above the river, shoulder blades pressing back hard against the Palisades. When I first drove down the Hudson Parkway it was bumpy and nerve-wracking, as if your car were being shot from a pinball machine down a slope into some rough forest. It was all unknown and possibility.

In 1980 New York was near bankruptcy, with garbage strikes every month, it seemed, and a crumbling, weedy infrastructure. These days, it gleams and towers in ways most people I know hate and can’t understand. Hugging the parkway in the West Sixties and Seventies is an ugly sheet of Trump buildings, a monument to urban corruption, soft money, and natives who should have taken to the streets saying nothing. Farther down the island, joggers, baby strollers, and blue and red bikes flow alongside a fluted, flower-filled river walkway alongside once-scary, now-forgotten docks, where gay men once met up in the dark for dates, hookups, and hookers in mink coats and high boots worked the nights until sunrise and breakfast.

The Westway, the old strip club on Clarkson Street, is still there, but today it’s owned by a hipster restaurant entrepreneur who caters to the ironic cultural lifestylers, more fashion world than art, people who are ”cool” because they live in New York. The little park with the basketball court is still on the corner of Spring and Thompson, an old slate-gray bookmark from an era otherwise written over by branded shops and shoppers from West Broadway down to Tribeca. Any place I depended on once to be deserted now teems with bodies and long black cars and faraway accents all day, all night.

When I first came to New York, the gallery building at 420 West Broadway housing both Leo Castelli and Mary Boone was pretty much all there was for big, established downtown galleries. The Dia Art Foundation stood across the street, and farther down you could find extremely raw but formal spaces that once housed “eternally” minimalist art like Walter De Maria’s “The Broken Kilometer.” Today Soho has been taken over by one echo-effect mall-friendly chain store after another: American Apparel, the Gap, Forever 21, H&M. No one else can afford the rents, I guess. Dave’s Luncheonette, the twenty-four-hour joint on Broadway and Canal, one stop after the Mudd Club, is long gone. Canal Jean, whose $5 bins fronting the sidewalk once dressed everyone I knew in bright-colored jeans and black tops, is another institution worn down and chased out. The Italian part of Little Italy is another seedy ghost. Its men’s clubs, empty except for espresso machines and ambiguous back-room goings-on, have disappeared. Maybe the methadone clinic on Spring Street where Sid Vicious used to go is still there. Otherwise, nothing’s left but the big Catholic church on Church Street, though today it’s being squeezed hard by boutiques and little specialty restaurants.

Overtaking Little Italy and the once mostly Jewish Lower East Side is Chinatown, forever edging outward, a mini-universe of fashionable, carefully dressed Asian women and storefronts resembling canal-side art installations. At night no one, me included, ever felt safe walking between Grand and Houston Streets anywhere east of the Bowery. For that matter, in Alphabet City no block east of Second Avenue to the river was safe—too many drug dealers. Today it’s all students, a melee of cheekbones and stubble and tight jeans. The scary park between Forsyth and Chrystie Streets has been reclaimed to the point where today kids actually play games there.

These days, when I’m in New York, I wonder, What’s this place all about, really? The answer is consumption and moneymaking. Wall Street drives the whole country, with the fashion industry as the icing. Everything people call fabulous or amazing lasts for about ten minutes before the culture moves on to the next thing. Creative ideas and personal ambition are no longer mutually exclusive. A friend recently described the work of an artist we both know as “corporate,” and it wasn’t a compliment. The Museum of Modern Art is like a giant midtown gift store.

New York City today is a city on steroids. It now feels more like a cartoon than anything real. But New York has never been ideal, and people have always complained sourly about the changing face of the city, the loss of authenticity.

When you study contemporary art in Los Angeles, New York is continuously touted as the only possible place to live and do art. It was always in my frame of vision as a possibility. I was still interested in dance, even taking ballet while I was in art school. I recall reading about the loose collection of New York City–based dancers who collaborated with filmmakers and composers to perform avant-garde pieces at the Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village. I was especially taken by the idea of Yvonne Rainer’s “No Manifesto.” Yvonne rebuffed all technique, all glamour, all theater in her dance. She focused instead on

the amazing, beautiful ordinariness of bodies in movement. The idea that a film could be dance blew my mind.

Everything seemed to be happening in New York, and I set my sights there once I was deemed a graduate of Otis. It wouldn’t be my first trip there. A few months earlier I’d taken the bus east on a reconnaissance mission, partly to check out the city, partly to escape a relationship with an older artist that I knew was bad for me. I knew that if I stayed in that relationship no one would ever take me seriously or treat me as anything other than an older guy’s bright young female protégée. I spent six months in New York before taking the bus back to L.A. to save up money to fund a possible future there.

Before I could leave I was involved in a car accident. It happened the same day Keller had his first psychotic episode after his graduation from Berkeley. I was sitting in a driveway in heavy Southern California traffic in my old VW Bug, waiting to turn onto Robertson Boulevard in Culver City, when a car driving down the street bashed into a second car. I’m the witness, I told myself, and just then that same car swerved up onto the sidewalk, hitting my VW and folding it up against a wall. My injuries weren’t serious—my back was sprained, I got a few stitches, and the incident was turned over to the insurance companies—but a year later the money I got from that accident would make life in New York possible.

Girl in a Band

Girl in a Band